Climate transition plans are coming to a jurisdiction near you. Regulators are broadly moving beyond mandatory disclosures of emissions and climate targets toward disclosure of the actions companies are planning to take to achieve those targets. Within a few years, most large companies will be required to specify precisely that in a transition plan as part of their disclosure requirements. As is often the case, Europe leads the way, but other jurisdictions will soon follow.

It’s a prospect that may not be universally welcomed. Many companies already struggle to stay on top of the steady flow of new regulations and expectations on sustainability topics. So far, most of the companies that have produced climate transition plans have approached it as an exercise for disclosure reasons, not always as a plan to integrate into their strategy and operations.

However, it’s a mistake to treat transition plans as just another compliance chore. Over time, investors and regulators won’t be satisfied with a transition plan alone; they will want to see the concrete results it delivers and, if they fall short, how companies are planning to correct course to catch up. Regulators don’t want a static transition plan but rather dynamic transition planning.

There is a second, more important reason for companies to get involved in transition planning: it is a great tool to convert broad climate goals into operational action in a systematic way, a step that many companies find challenging. So, instead of delaying, companies should leverage transition planning to transform their business model for a just, low-carbon future.

This article explores the trend toward mandatory transition plans, the business case of transition planning, and how companies can get started.

1. Transition plan - from nice-to-have to got-to-do

The concept of transition plans has been around in various voluntary disclosure frameworks for a while. However, the fact that regulatory bodies have started or signalled intent to mandate Transition Plan disclosures is new. The table below summarises the most important disclosure frameworks with a Transition Plan requirement.

The specific criteria of a transition plan vary somewhat from disclosure standard to disclosure standard. However, the publication in October 2023 of the Transition Plan Disclosure framework by the Transition Plan Taskforce (TPT) in the United Kingdom has led to an increased convergence of what a Transition Plan should entail. The comprehensive TPT framework goes well beyond emissions and includes equity and social requirements, which are crucial to achieving a just transition.

Although launched in the UK, the TPT is de facto developing into the global gold standard for Transition Plans, even more so now that the International Sustainability Standards Board (ISSB) will assume responsibility for the TPT disclosure framework and related guidance when TPT sunsets in October 2024.

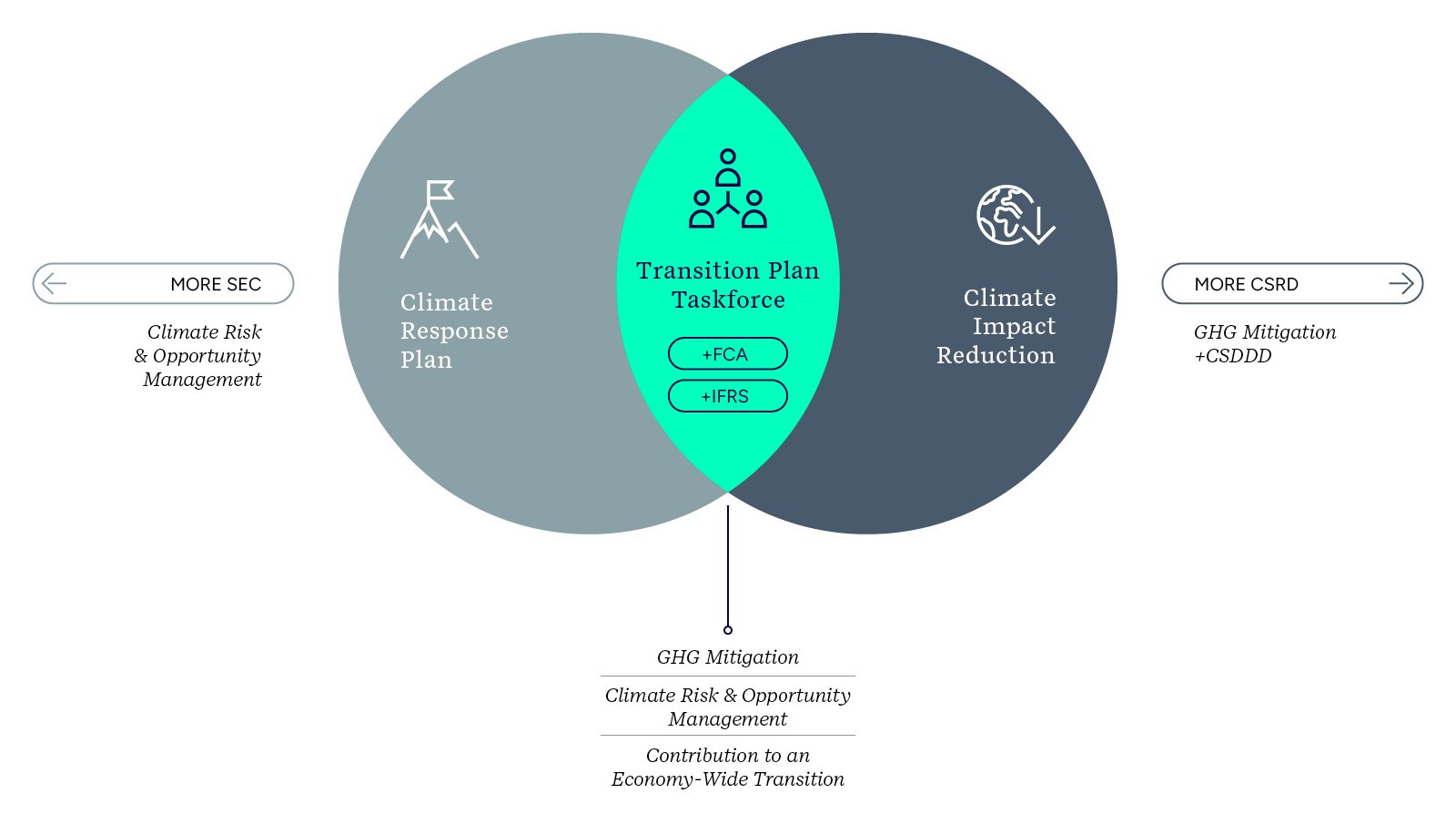

As the diagram below shows, transition plans can be split into three categories: plans that mainly require a focus on response to climate risks and opportunities, plans that mainly require a focus on greenhouse gas mitigation, and ones that require a focus on both.

Graph1: Taking the middle ground

The diagram places the SEC Climate Rule and the CSRD and CSDDD on the opposite ends of the spectrum, while the FCA’s sustainability disclosure requirements and ISSB, which are set to follow the TPT framework, are in the middle. This is important to consider when companies choose a transition plan approach: more comprehensive transition plans will make them more resilient to climate risks and better prepared to seize commercial opportunities of a low-carbon future.

The trend towards transition plans as part of mandatory disclosures is steady and irreversible, and companies should prepare themselves. Luckily, companies that must comply with several disclosure standards do not need completely different transition plans for each. Although there are differences across plans and requirements regarding objectives, strategy, actions, GHG mitigation, and low-carbon economy alignment are broadly similar.

However, as we mentioned earlier, drafting a transition plan should not be the end goal but the starting point of a dynamic transition planning process.

2. The business case for transition planning

Embedding transition planning into operations will promote value protection and creation and accelerate the transition to a just, low-carbon economy. But before focusing on how transition planning contributes to these positive outcomes, let’s first highlight the risks of not doing it.

- Apart from the obvious risk of looming regulatory non-compliance, investors and other stakeholders could conclude that a company lacks ambition and is flouting its responsibilities, which introduces reputational or litigation risk in an increasing number of markets.

- It will erode investor, lender and other stakeholder confidence that the company has climate issues under control and is sufficiently on top of market, technology, and policy trends to maintain a competitive position. A significant number of Transition Plans have been put to a shareholder vote, and the Say on Climate initiative tracks these and appears to be gathering momentum.

- It will put value creation at risk since business transformations take time, and a lack of robust transition planning delays the necessary action, sense of urgency, and cultural shifts needed for a whole company transition.

Companies should see developing a transition plan and its operational implementation as a business opportunity. It builds resilience and supports the operationalization of broad climate and potentially other sustainability goals in two critical ways.

- It pushes companies toward a cross-functional strategy that brings business/commercial and sustainability/climate strategy under the same process, which is one of the thorny parts of putting broad goals into action. It will lay the foundation for a value-driven decarbonization process and the achievement of net-zero goals.

- It encourages proactive management of complex issues facing the business and the steps the organization takes to position itself for future success.

Both elements show that if done well and comprehensively, transition planning can make the difference between organizational success and failure during the transition to a low-carbon economy. Potential positive outcomes are listed below.

Positive outcomes of a value-driven decarbonization strategy

- Providing a North Star or blueprint for business strategy and direction, which becomes a reference point for the organization and its people, with the potential to positively influence culture and retention.

- Revenue protection and/ or growth from innovation, new customer demands, and, in some cases, price premiums.

- Cost management opportunities, whether through reduced exposure to volatility, carbon, or better investment timing

- Better supply chain dynamics as those favourably positioned or with first mover advantage grow market share or exert supplier/ buyer power

Positive outcomes of proactive management of climate issues and opportunities

- Increased revenue and market share opportunities through innovation and providing low-carbon products, services, and energy transition solutions.

- Accessing capital, including sustainable finance, potentially at a lower cost by showing alignment with investor and lender net zero targets and pathways.

- Communicating with other stakeholders, e.g., customers and suppliers, purposeful management of climate issues, which could align with the ambitions of others in the value chain and mitigate reputation and legal risk.

- Attracting the best talent – to transition successfully, organizations will need people with the right skillsets, many of whom increasingly want to work at organizations proactively tackling sustainability issues

3. State of existing plans - room for improvement

The early signs are that most companies are far away from fully leveraging the value transition planning can provide. After assessing dozens of transition plan disclosures, we conclude that many are incomplete and lack internal coherence or specificity. Very few companies seem ready to take it one logical step further and use a robust transition plan as the starting point for a dynamic transition planning process.

Many transition plans that try to follow the TPT disclosure framework are first attempts, such as HSBC, H&M, and Bayer. Others are the first update, like Unilever. Increasing numbers of companies are putting their transition plan to a shareholder vote, which may add scrutiny but also requires the knowledge to properly assess the quality of transition plans, a capacity the finance sector currently does not possess. So, even though transition plans are quickly becoming the norm, their level of sophistication is still quite limited.

This reality is confirmed by an assessment of 2023 transition plan disclosures by the Carbon Disclosure Project (CDP). It concludes that of 23,000 CDP participants, only 140 companies disclosed against all 21 of CDP’s climate transition plan indicators. Since CDP is a benchmark of credibility, organizations are clearly struggling with some key aspects of transition planning. Below is a list of transition plan elements currently lacking credibility, and, if available, examples of companies that do get it right.

Developing a coherent, consistent, and credible transition plan is difficult. But done right, it serves as the foundation for setting up a dynamic transition planning process. So, companies should not treat a transition plan as a point-in-time disclosure but as a crucial first step in the overarching process of integrating climate transition planning into their operations and business/ commercial strategy, including annual budgeting. Organizations that succeed in doing that are much more likely to be both credible and commercially successful in the medium to long term.

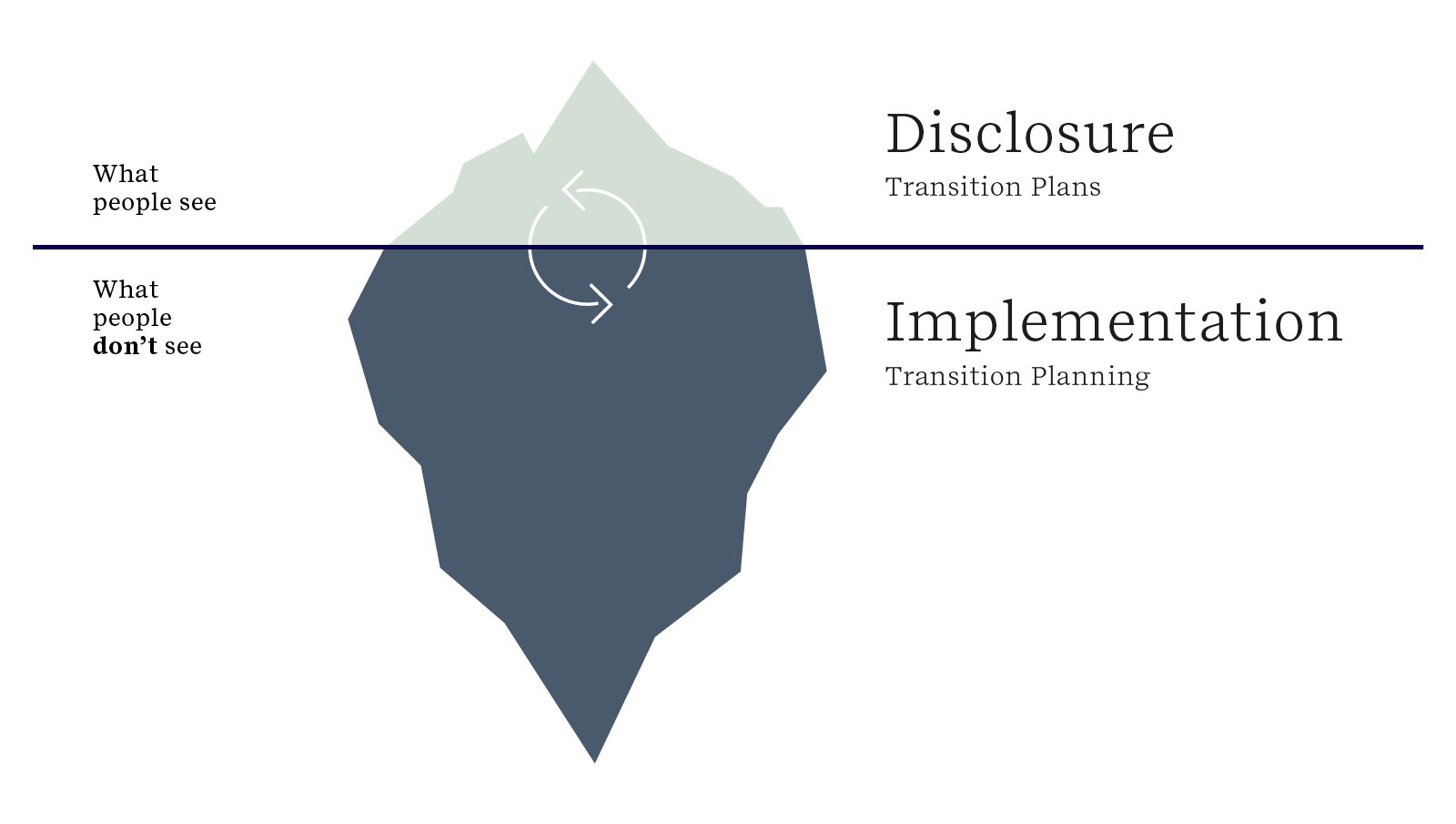

The implementation iceberg - from plan to planning

So if the transition plan itself, either the internal plan or the disclosure, is merely the ‘tip of the iceberg,’ how should companies approach the seemingly overwhelming work that needs to be done beyond setting the strategy and action plan for just one cycle?

Graph 2: Tip of the iceberg

Moving from a static transition plan to dynamic transition planning won’t happen overnight. It will take substantial organizational change and challenge many default ways of working, both operationally and in ways departments collaborate and communicate. No doubt, it will take much trial and error to get it right. But the rewards are worth it, and regulatory trends demand it. Below are some recommendations on how companies can kickstart the process.

5. Conclusion - Don't procrastinate

Companies get pulled in many directions, from geopolitical events and regulations to supply chain troubles. And since many transition-plan-related specifics are still uncertain, it can be tempting for companies to put off thinking about it. But uncertainty doesn’t rule out urgency. And it’s clear that no matter the loose ends, regulators, investors, and other stakeholders want companies to make progress on transition planning fast. It’s up to companies to figure out how to do it.

Investing time, capacity, and money into transition planning will also help companies get over the biggest bottleneck to integrating sustainability into business: translating corporate climate goals into effective operational and commercial action. So, companies that want to be prepared for the risks and opportunities of a low-carbon future should start building transition planning capacity today. Anything else is a business risk waiting to happen.